Tensor product of fields

In abstract algebra, the theory of fields lacks a direct product: the direct product of two fields, considered as a ring is never itself a field. On the other hand it is often required to 'join' two fields K and L, either in cases where K and L are given as subfields of a larger field M, or when K and L are both field extensions of a smaller field N (for example a prime field).

The tensor product of fields is the best available construction on fields with which to discuss all the phenomena arising. As a ring, it is sometimes a field, and often a direct product of fields; it can, though, contain non-zero nilpotents (see radical of a ring).

If K and L do not have isomorphic prime fields, or in other words they have different characteristics, they have no possibility of being common subfields of a field M. Correspondingly their tensor product will in that case be the trivial ring (collapse of the construction to nothing of interest).

Contents |

Compositum of fields

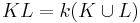

Firstly, we will define the notion of the compositum of fields. This construction occurs frequently in field theory. The idea behind the compositum is to make the smallest field containing two other fields. In order to formally define the compositum, we must first specify a tower of fields. Let k be a field and L and K be two extensions of k. The compositum, denoted KL is defined to be  where the right hand side denotes the extension generated by K and L. Note that this assumes some field containing both K and L. Either one starts in a situation where such a common over-field is easy to identify (for example if K and L are both subfields of the complex numbers); or one proves a result that allows one to place both K and L (as isomorphic copies) in some large enough field.

where the right hand side denotes the extension generated by K and L. Note that this assumes some field containing both K and L. Either one starts in a situation where such a common over-field is easy to identify (for example if K and L are both subfields of the complex numbers); or one proves a result that allows one to place both K and L (as isomorphic copies) in some large enough field.

In many cases we can identify K.L as a vector space tensor product, taken over the field N that is the intersection of K and L. For example if we adjoin to the rational field Q √2 to get K, and √3 to get L, it is true that the field M obtained as K.L inside the complex numbers C is (up to isomorphism)

as a vector space over Q. (This type of result can be verified, in general, by using the ramification theory of algebraic number theory.)

Subfields K and L of M are linearly disjoint (over a subfield N) when in this way the natural N-linear map of

to K.L is injective.[1] Naturally enough this isn't always the case, for example when K = L. When the degrees are finite, injective is equivalent here to bijective.

A significant case in the theory of cyclotomic fields is that for the n-th roots of unity, for n a composite number, the subfields generated by the pkth roots of unity for prime powers dividing n are linearly disjoint for distinct p.[2]

The tensor product as ring

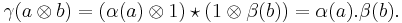

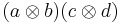

To get a general theory, we need to consider a ring structure on  . We can define the product

. We can define the product  to be

to be  . This formula is multilinear over N in each variable; and so defines a ring structure on the tensor product, making

. This formula is multilinear over N in each variable; and so defines a ring structure on the tensor product, making  into a commutative N-algebra, called the tensor product of fields.

into a commutative N-algebra, called the tensor product of fields.

Analysis of the ring structure

The structure of the ring can be analysed, by considering all ways of embedding both K and L in some field extension of N. Note for this that the construction assumes the common subfield N; but does not assume a priori that K and L are subfields of some field M (thus getting round the caveats about constructing a compositum field). Whenever we embed K and L in such a field M, say using embeddings α of K and β of L, there results a ring homomorphism γ from  into M defined by:

into M defined by:

The kernel of γ will be a prime ideal of the tensor product; and conversely any prime ideal of the tensor product will give a homomorphism of N-algebras to an integral domain (inside a field of fractions) and so provides embeddings of K and L in some field as extensions of (a copy of) N.

In this way one can analyse the structure of  : there may in principle be a non-zero Jacobson radical (intersection of all prime ideals) - and after taking the quotient by that we can speak of the product of all embeddings of K and L in various M, over N.

: there may in principle be a non-zero Jacobson radical (intersection of all prime ideals) - and after taking the quotient by that we can speak of the product of all embeddings of K and L in various M, over N.

In case K and L are finite extensions of N, the situation is particularly simple, since the tensor product is of finite dimension as an N-algebra (and thus an Artinian ring). We can then say that if R is the radical we have  a direct product of finitely many fields. Each such field is a representative of an equivalence class of (essentially distinct) field embeddings for K and L in some extension of M.

a direct product of finitely many fields. Each such field is a representative of an equivalence class of (essentially distinct) field embeddings for K and L in some extension of M.

Examples

For example, if K is generated over Q by the cube root of 2, then  is the product of (a copy of) K, and a splitting field of

is the product of (a copy of) K, and a splitting field of

- X3 − 2,

of degree 6 over Q. One can prove this by calculating the dimension of the tensor product over Q as 9, and observing that the splitting field does contain two (indeed three) copies of K, and is the compositum of two of them. That incidentally shows that R = {0} in this case.

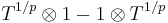

An example leading to a non-zero nilpotent: let

- P(X) = Xp − T

with K the field of rational functions in the indeterminate T over the finite field with p elements. (See separable polynomial: the point here is that P is not separable). If L is the field extension K(T1/p) (the splitting field of P) then L/K is an example of a purely inseparable field extension. In  the element

the element

is nilpotent: by taking its pth power one gets 0 by using K-linearity.

Classical theory of real and complex embeddings

In algebraic number theory, tensor products of fields are (implicitly, often) a basic tool. If K is an extension of Q of finite degree n,  is always a product of fields isomorphic to R or C. The totally real number fields are those for which only real fields occur: in general there are r1 real and r2 complex fields, with r1 + 2r2 = n as one sees by counting dimensions. The field factors are in 1-1 correspondence with the real embeddings, and pairs of complex conjugate embeddings, described in the classical literature.

is always a product of fields isomorphic to R or C. The totally real number fields are those for which only real fields occur: in general there are r1 real and r2 complex fields, with r1 + 2r2 = n as one sees by counting dimensions. The field factors are in 1-1 correspondence with the real embeddings, and pairs of complex conjugate embeddings, described in the classical literature.

This idea applies also to  where Qp is the field of p-adic numbers. This is a product of finite extensions of Qp, in 1-1 correspondence with the completions of K for extensions of the p-adic metric on Q.

where Qp is the field of p-adic numbers. This is a product of finite extensions of Qp, in 1-1 correspondence with the completions of K for extensions of the p-adic metric on Q.

Consequences for Galois theory

This gives a general picture, and indeed a way of developing Galois theory (along lines exploited in Grothendieck's Galois theory). It can be shown that for separable extensions the radical is always {0}; therefore the Galois theory case is the semisimple one, of products of fields alone.

See also

- Extension of scalars—tensor product of a field extension and a module over that field

Notes

- ^ Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Linearly-disjoint extensions", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=L/l059560

- ^ Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Cyclotomic field", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=c/c027570

References

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Compositum of field extensions", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=C/c024310

- George Kempf (1995) Algebraic Structures, pp. 85–87.

- Algebraic Number Theory, J. S. Milne Notes (PDF) at p. 17.

- A Brief Introduction to Classical and Adelic Algebraic Number Theory, William Stein (PDF) pp. 140–142.

- Zariski, Oscar; Samuel, Pierre (1975) [1958], Commutative algebra I, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 28, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-0-387-90089-6, MR0090581